I Don’t Believe in God but I Believe in Troy Polamalu

by Bob Pajich

Troy Polamalu is standing on the floor of a StarKist tuna manufacturing plant on the island of

Pago Pago in American Samoa in front of hundreds of round-faced women in hair nets and

yellow t-shirts.

Like everyone, he is crying.

The women just finished serenading Polamalu with a song sung in Samoan. The only Samoan I speak is Steelers, and mainly Fu — Chris Fuamatu-Ma'afala. And the only word I know is

Fuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu!!!!!!

Still, the emotion in this ancient song that was carried like treasure and passed down as if it was as priceless as air and water and fish and family clearly shines through. It’s haunting, beautiful, deep, positive, sad, soulful and, somehow, very, very American.

Troy is in tears as he holds the microphone. The lei they gave him is the yellow of the Three

Sister Bridges over the Allegheny, his shirt black with white flowers stitched up the side.

He goes to speak but can’t. Twenty-seconds go by, a woman shouts “We love you Troy” and they all start clapping and cheering again. Polamalu bows his head, pinches the bridge of his nose and collects himself. Tears require gravity and the gravity here is as strong as on Jupiter.

He speaks slow, quietly and carefully, which has become as big of a trademark as his hair

flowing from the back of his helmet when he used his body to destroy people.

“If God decides not to give me anymore days to repent for my many sins, I would die today a

very happy man.”

He calls them all his mothers. He dances for them. His presence and words affirm their place in the world, in this universe, both spiritually and physically, and it’s strange and wonderful and achingly sad — these are poor, blue-collar workers, the daughters of the same, the

granddaughters and grandsons of the same.

That’s how Troy feels about a lot of us Pittsburghers, or the idea of “Pittsburgh,” and he says as much reflecting on the visit to the factory.

“If Pittsburgh and the Steelers represent anything in this country, we represent blue-collar

workers, and that is the epitome those workers are doing. It was really touching,” he says in the mini-documentary “Homecoming King Troy Polamalu’s Return Home.”

Is it an undeserved cliche? The cynic inside me says yes, but I’m a little tired of that guy. That

guy needs to be dipped in a vat of acid or make a pilgrimage somewhere that will turn his cells

into light, but nothing comes to mind except a playoff game in Pittsburgh with the stadium filled and the stands shaking like it did when I watched Troy Polamalu pick off Joe Flacco in the 2008 AFC Championship game and take it to the house, sealing the game, which is about as far as you can get from a tuna fish factory in Samoa experiencing layoffs.

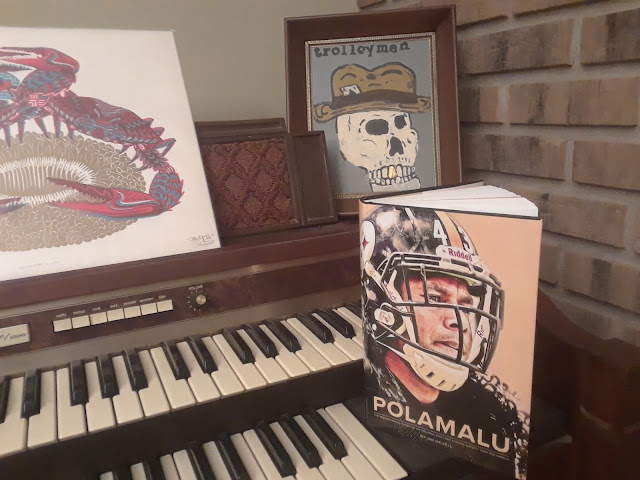

I don’t believe in God but I believe in Troy Polamalu and thank Polamalu for Jim Wexell’s

“Polamalu - The Inspirational Story of Pittsburgh Steelers Strong Safety Troy Polamalu.”

This biography is perfect for Steelers fans who not only thrive on the details and anecdotes that make following them so fun, but also those who could use a good solid whack to knock off all the terrible rust and be reminded of some of the basic things that feed the human soul.

“Polamalu” is a massive collection of interviews with teammates, family members, pastors and

friends who universally celebrate this unique man.

The Steelers who go on record include Brett Keisel, Ryan Clark, Alan Faneca, James Harrison,

Chris Hoke, Mike Logan, Joey Porter, and Ike Taylor. Coaches include Mike Tomlin, Dick

LeBeau, Bill Cowher, Darren Perry and Carnell Lake.

There are also many interviews with Troy’s family members, including his aunt and uncle who

helped raise him in Oregon, his cousins and Troy’s uncle, Kennedy Polamalu, who, like Troy,

played at the University of Southern California. He’s a long-time running backs coach who

helped the Jags beat the Steelers in the 2008 playoffs and is still in the NFL.

Wexell shows how Troy’s career unfolds, from his early days simply as a boy, to his career at

USC, to the 12-year adventure he had with the Pittsburgh Steelers. To a person, the cast of

characters share intimate and sincere stories highlighting why Troy Polamalu is a Hall of Fame NFLer and human being.

Wexell modeled “Polamalu” after Alan Paul’s books on The Allman Brothers Band and Stevie

Ray Vaughn. Wexell sets the scene and then let subjects fill in the blanks, in their own words.

The book reads sort of like a script, with narrative and background connecting dialogue.

It’s noted in the intro Wexell “asked Alan if I could not only steal his style but if he would edit

this book. Who better to edit a stolen style than the guy from whom you are stealing? As a

lifelong Steelers fan from Squirrel Hill, Paul, the accomplished rock-and-roll author, said yes to both requests.”

Wexell calls himself the “collector and collator” of this book, but that sells himself short. His

writing is straightforward and informative, intertwined with moments of really good storytelling and wit. A Pittsburgh sports writer veteran who got his start as a teenager in the 70s at the Standard Observer, Wexell says the Universe assigned him “Polamalu,” and he does a great job as the celestial conductor, keeping everything moving along seamlessly.

A combination of the admiration, awe and love they felt toward Polamalu, and the

professionalism and writer/editor’s eye of Wexell, surely set the “cast of characters” (listed

helpfully in front of the book) at ease and allowed them to comfortably spill the goods on Troy.

Even though Polamalu would not sit for an interview for this book, Wexell has him on record as part of his job interviewing players as a Steelers beat reporter. He also relies on the work of other reporters, many of which he shares kind words about, and the vast Reference List/Notes is one of the reasons fans of Troy would want to own “Polamalu.”

He also swears Polamalu, who, in the later part of his playing days, knew Wexell wanted to write his biography, gave him nuggets of information with a wink and nod during media scrums, sometimes even saying that one was for Jim.

Wexell’s ability as a researcher and editor is apparent, as is his eye for humor. Brett Keisel is

funny. Joey Porter is funny. James Harrison is terrifying. And funny. And, like everyone else in this book, a huge fan of Troy Polamalu.

There’s a sense of enlightenment, too, something way beyond the violent and messy sport of

football. There are secrets and ideas about living a well-rounded, fulfilling life, about the virtues of hard work, about how to try to find truth within, and how that varies from person to person.

Over and over Polamalu is defined as being special, being different. Intensely religious, God

lives in everything surrounding Troy. He brings it with him with trinkets and conversations and prayers and through the way he goes about work. I’m sure he’s considered a holy man by many of the people he knows, and even strangers, whose tears cannot resist this man’s gravity.

People are attracted to Troy in part because of the great contrast, the duality, of his personality and his former job. Tasmanian devil on the field, soft-voiced, philosophical thinker off, it truly can be a mind-teaser.

Polamalu, who I would consider a non-violent man, was one of the best players at one of the

most violent positions in maybe the most violent game on the planet. He thrived within it and

mercilessly threw his body where it was needed on the field, consequences to him or his

opponents be damned.

This is just a guess, but Polamalu liked football because of the test it gave him, the friends he

made. He liked football because it brought out the physical and mental best he could be at that

moment in his life and, if you didn’t prepare properly, there was real consequence to face.

Humiliation. Embarrassment. Unemployment. Paralysis.

No matter how hard he trained, how early he got to campus, how well he took care of his body

and mind, one day he would pay for playing football. The life that God gave him would be

chiseled away by this game.

Longterm, the list goes on with example after example of the horrendous lives of former players. See Tony Dorsett. Justin Strelzyk. Terry Long. Jovan Belcher. Dave Duerson. Mike Webster. Junior Seau. Polamalu was very aware of these men.

Still, Polamalu hated the NFL’s push to make the league “safer.” He did not approve of the

violence being removed from the game, a move the NFL made thanks in part to the Steelers

defenses he anchored that sent multiple people to the ER. Removing consequence diluted the

game and the sacrifice and courage it required to be great within it.

His manhood, a part of his spiritual philosophy, relied on the fact that in order to play

professional football properly, the way his God himself intended it, required men to be willing to sacrifice everything, including their future years as a human being just walking the Earth and remembering their children’s middle names or where they put their car keys.

There’s no doubt the hits Polamalu made took months or even years away from both his

opponents and his own life. There’s an edge here I’m trying to understand, have always tried to understand as a writer and also a man who likes blood sports.

Would it make more sense if I believed in an afterlife? Maybe. No matter what, the journey goes on until it doesn’t. Even though there’s no real answers here in “Polamalu,” there’s movement and thought, thanks to both Troy and Wexell and everyone in it.

Polamalu said this when asked, yet again, if he even liked football:

“Truthfully, I love life, and if you love life, there’s nothing that you can really find in life that

could really disappoint you, whether it’s something that you dislike or something that you like.”

You can hear his voice, can’t you? That soft, curious lilt. The sincerity. It’s almost holy. Beatific. Calming. And a bit strange, a bit different, not because it comes from a football player, but from an American.

“Polamalu” is Wexell’s fourth book, the second from his own Pittsburgh Sports Publishing

Company.

by Bob Pajich

Troy Polamalu is standing on the floor of a StarKist tuna manufacturing plant on the island of

Pago Pago in American Samoa in front of hundreds of round-faced women in hair nets and

yellow t-shirts.

Like everyone, he is crying.

The women just finished serenading Polamalu with a song sung in Samoan. The only Samoan I speak is Steelers, and mainly Fu — Chris Fuamatu-Ma'afala. And the only word I know is

Fuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu!!!!!!

Still, the emotion in this ancient song that was carried like treasure and passed down as if it was as priceless as air and water and fish and family clearly shines through. It’s haunting, beautiful, deep, positive, sad, soulful and, somehow, very, very American.

Troy is in tears as he holds the microphone. The lei they gave him is the yellow of the Three

Sister Bridges over the Allegheny, his shirt black with white flowers stitched up the side.

He goes to speak but can’t. Twenty-seconds go by, a woman shouts “We love you Troy” and they all start clapping and cheering again. Polamalu bows his head, pinches the bridge of his nose and collects himself. Tears require gravity and the gravity here is as strong as on Jupiter.

He speaks slow, quietly and carefully, which has become as big of a trademark as his hair

flowing from the back of his helmet when he used his body to destroy people.

“If God decides not to give me anymore days to repent for my many sins, I would die today a

very happy man.”

He calls them all his mothers. He dances for them. His presence and words affirm their place in the world, in this universe, both spiritually and physically, and it’s strange and wonderful and achingly sad — these are poor, blue-collar workers, the daughters of the same, the

granddaughters and grandsons of the same.

That’s how Troy feels about a lot of us Pittsburghers, or the idea of “Pittsburgh,” and he says as much reflecting on the visit to the factory.

“If Pittsburgh and the Steelers represent anything in this country, we represent blue-collar

workers, and that is the epitome those workers are doing. It was really touching,” he says in the mini-documentary “Homecoming King Troy Polamalu’s Return Home.”

Is it an undeserved cliche? The cynic inside me says yes, but I’m a little tired of that guy. That

guy needs to be dipped in a vat of acid or make a pilgrimage somewhere that will turn his cells

into light, but nothing comes to mind except a playoff game in Pittsburgh with the stadium filled and the stands shaking like it did when I watched Troy Polamalu pick off Joe Flacco in the 2008 AFC Championship game and take it to the house, sealing the game, which is about as far as you can get from a tuna fish factory in Samoa experiencing layoffs.

I don’t believe in God but I believe in Troy Polamalu and thank Polamalu for Jim Wexell’s

“Polamalu - The Inspirational Story of Pittsburgh Steelers Strong Safety Troy Polamalu.”

This biography is perfect for Steelers fans who not only thrive on the details and anecdotes that make following them so fun, but also those who could use a good solid whack to knock off all the terrible rust and be reminded of some of the basic things that feed the human soul.

“Polamalu” is a massive collection of interviews with teammates, family members, pastors and

friends who universally celebrate this unique man.

The Steelers who go on record include Brett Keisel, Ryan Clark, Alan Faneca, James Harrison,

Chris Hoke, Mike Logan, Joey Porter, and Ike Taylor. Coaches include Mike Tomlin, Dick

LeBeau, Bill Cowher, Darren Perry and Carnell Lake.

There are also many interviews with Troy’s family members, including his aunt and uncle who

helped raise him in Oregon, his cousins and Troy’s uncle, Kennedy Polamalu, who, like Troy,

played at the University of Southern California. He’s a long-time running backs coach who

helped the Jags beat the Steelers in the 2008 playoffs and is still in the NFL.

Wexell shows how Troy’s career unfolds, from his early days simply as a boy, to his career at

USC, to the 12-year adventure he had with the Pittsburgh Steelers. To a person, the cast of

characters share intimate and sincere stories highlighting why Troy Polamalu is a Hall of Fame NFLer and human being.

Wexell modeled “Polamalu” after Alan Paul’s books on The Allman Brothers Band and Stevie

Ray Vaughn. Wexell sets the scene and then let subjects fill in the blanks, in their own words.

The book reads sort of like a script, with narrative and background connecting dialogue.

It’s noted in the intro Wexell “asked Alan if I could not only steal his style but if he would edit

this book. Who better to edit a stolen style than the guy from whom you are stealing? As a

lifelong Steelers fan from Squirrel Hill, Paul, the accomplished rock-and-roll author, said yes to both requests.”

Wexell calls himself the “collector and collator” of this book, but that sells himself short. His

writing is straightforward and informative, intertwined with moments of really good storytelling and wit. A Pittsburgh sports writer veteran who got his start as a teenager in the 70s at the Standard Observer, Wexell says the Universe assigned him “Polamalu,” and he does a great job as the celestial conductor, keeping everything moving along seamlessly.

A combination of the admiration, awe and love they felt toward Polamalu, and the

professionalism and writer/editor’s eye of Wexell, surely set the “cast of characters” (listed

helpfully in front of the book) at ease and allowed them to comfortably spill the goods on Troy.

Even though Polamalu would not sit for an interview for this book, Wexell has him on record as part of his job interviewing players as a Steelers beat reporter. He also relies on the work of other reporters, many of which he shares kind words about, and the vast Reference List/Notes is one of the reasons fans of Troy would want to own “Polamalu.”

He also swears Polamalu, who, in the later part of his playing days, knew Wexell wanted to write his biography, gave him nuggets of information with a wink and nod during media scrums, sometimes even saying that one was for Jim.

Wexell’s ability as a researcher and editor is apparent, as is his eye for humor. Brett Keisel is

funny. Joey Porter is funny. James Harrison is terrifying. And funny. And, like everyone else in this book, a huge fan of Troy Polamalu.

There’s a sense of enlightenment, too, something way beyond the violent and messy sport of

football. There are secrets and ideas about living a well-rounded, fulfilling life, about the virtues of hard work, about how to try to find truth within, and how that varies from person to person.

Over and over Polamalu is defined as being special, being different. Intensely religious, God

lives in everything surrounding Troy. He brings it with him with trinkets and conversations and prayers and through the way he goes about work. I’m sure he’s considered a holy man by many of the people he knows, and even strangers, whose tears cannot resist this man’s gravity.

People are attracted to Troy in part because of the great contrast, the duality, of his personality and his former job. Tasmanian devil on the field, soft-voiced, philosophical thinker off, it truly can be a mind-teaser.

Polamalu, who I would consider a non-violent man, was one of the best players at one of the

most violent positions in maybe the most violent game on the planet. He thrived within it and

mercilessly threw his body where it was needed on the field, consequences to him or his

opponents be damned.

This is just a guess, but Polamalu liked football because of the test it gave him, the friends he

made. He liked football because it brought out the physical and mental best he could be at that

moment in his life and, if you didn’t prepare properly, there was real consequence to face.

Humiliation. Embarrassment. Unemployment. Paralysis.

No matter how hard he trained, how early he got to campus, how well he took care of his body

and mind, one day he would pay for playing football. The life that God gave him would be

chiseled away by this game.

Longterm, the list goes on with example after example of the horrendous lives of former players. See Tony Dorsett. Justin Strelzyk. Terry Long. Jovan Belcher. Dave Duerson. Mike Webster. Junior Seau. Polamalu was very aware of these men.

Still, Polamalu hated the NFL’s push to make the league “safer.” He did not approve of the

violence being removed from the game, a move the NFL made thanks in part to the Steelers

defenses he anchored that sent multiple people to the ER. Removing consequence diluted the

game and the sacrifice and courage it required to be great within it.

His manhood, a part of his spiritual philosophy, relied on the fact that in order to play

professional football properly, the way his God himself intended it, required men to be willing to sacrifice everything, including their future years as a human being just walking the Earth and remembering their children’s middle names or where they put their car keys.

There’s no doubt the hits Polamalu made took months or even years away from both his

opponents and his own life. There’s an edge here I’m trying to understand, have always tried to understand as a writer and also a man who likes blood sports.

Would it make more sense if I believed in an afterlife? Maybe. No matter what, the journey goes on until it doesn’t. Even though there’s no real answers here in “Polamalu,” there’s movement and thought, thanks to both Troy and Wexell and everyone in it.

Polamalu said this when asked, yet again, if he even liked football:

“Truthfully, I love life, and if you love life, there’s nothing that you can really find in life that

could really disappoint you, whether it’s something that you dislike or something that you like.”

You can hear his voice, can’t you? That soft, curious lilt. The sincerity. It’s almost holy. Beatific. Calming. And a bit strange, a bit different, not because it comes from a football player, but from an American.

“Polamalu” is Wexell’s fourth book, the second from his own Pittsburgh Sports Publishing

Company.

Bob Pajich is a writer living in East McKeesport. His latest poetry collection Panda Magic was published in 2020.

Love "The Pittsburgh Book Review" and this post is, hands down, the best yet. Cheers, Bob (and Kris).

ReplyDelete